I attended the on building height not intending to speak. But after listening to dozens of impassioned presentations, I submitted my card because no one mentioned the morbidly obese elephant in the room: the high cost of parking cars.

The Council Chambers looked like a living Xmas tree: people dressed in red for Historical Society solidarity and the 2-story height limit, while an equal number wore green for the .

Unaware of the necessity of wearing team colors to the meeting, I wore a bright red shirt. But I’m not taking sides in this debate.

My focus is solely on transportation because how we move affects how we interact with each other, how we create our public spaces, our Village Character, our quality of life, and our public windows to the sea.

Transportation also affects our property rights. That soft-spoken, big elephant in the Council Chambers persisted through all the presentations, on all sides, frolicking just below the surface of every argument. It seemed most people were unaware of its presence, but there was one subtle clue.

- During the meeting, San Clemente Architect, Michael Luna, showed a ground-level floor plan of a typical downtown lot. Approximately 50% of the lot surface was dedicated to parking cars. (Michael added from the gallery: “at least 50%”).

I recalled for our Planning Commission that, back in 2009, the approval of Nick’s Restaurant on Del Mar was controversial not because of the quality of the food or architectural details, but because of its projected parking requirement. As a City Planning Commissioner, I voted against that project for that reason. I would vote differently today.

So, why do we need so much land earmarked for parking?It’s not because we don’t like exercise. It’s not because most of us live so far away. The reason is the obvious: because so many people drive. But why?

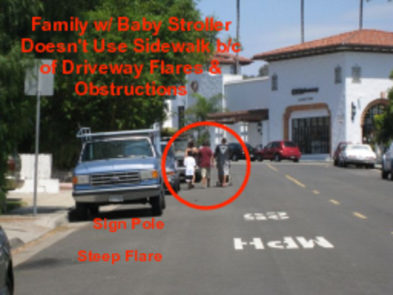

People feel unsafe walking because they have to share the roadway with cars.

- The pedestrian environment connecting neighborhoods to downtown destinations–not to mention schools–is so dangerous that people feel they MUST drive to ensure their own personal safety.

People use their own cars to protect themselves from other people’s cars.

Like many towns, our Spanish Village was not designed to integrate motorized and non-motorized modes of travel. That’s not the fault of present leadership and staff, all of whom are striving to improve the situation.

Yet as the density of San Clemente’s older neighborhoods has increased, the number of cars, courteously driven by some anddangerously by others, has increased.

We’ve all experienced these situations:

- Many drivers disregard the 25 mph residential speed limit.

- Many don’t stop at stop signs with cross walks.

- Many more drive at least the speed limit despite the close proximity of pedestrians.

- Even disabled pedestrians.

- Drivers don’t seem to care.

Here’s a case in point:

My neighbor, a former public official here in San Clemente, has had a minor stroke, is fighting a serious illness, and must now use a wheelchair because she’s too weak to walk. She turns 75 in a few days.

The only ADA accessible facilities in the old part of our village lie in the most inhospitable of places: the roadway. When she was stronger, my neighbor used a cane, her free hand holding her escort’s arm.

We take precautions, controlling as many variables as we can:

- We plan our relative body positions in the roadway.

- She’d be on the inside and I’d be on the outside, closer to moving cars.

- Sometimes, I wear my fluorescent retroreflective safety vest even in the daytime. It’s that dicey out there.

But what are my neighbor’s options? Expend her limited energy to get to the car, have someone drive her to the beach trail, then struggle to get to its non-motorized path and back?

She chooses to walk in the street for 15 minutes to get stronger so she doesn’t sit in a chair and get weaker. We all know where the latter ends. What kind of choice is that?

But let’s get back to the topic at hand: building height and the parking of cars. Follow the logical pathway:

- People feel safer driving a car a walkable distance because their own car protects them from other people’s cars.

- Upon reaching their downtown destination by automobile, residents must park those cars.

- Local businesses have to earmark expensive private property to store those cars–all of which is free to the driver.

- Who pays? The property owner absorbs most of that cost, as only a limited amount can be passed on to the commercial tenant in the form of rent.

- As a result, business viability is unintentionally pitted against the need to temporarily store cars.

So, how does the landowner recoup the land revenue lost to parking cars? He/she needs to add more square footage for lease or sale. Mixed-use is viewed as the way to go: commercial on the bottom and residential on the top.

- The owner has to build up, not horizontally, because a large percentage of the commercial ground floor is required for–the cars–so it cannot be used to generate money. To justify renovation costs, landowners say they need to build two more stories because people don’t want to do everything in one small floor plan. That makes 3 stories total.

- And that, in turn, makes for rancorous community debate: architectural diversity and property rights vs. a man-made concrete canyon and preserving Ole’s Vision. Green shirts vs. red shirts.

- Then we have conflict: parking vs. pedestrians.

It doesn’t have to be that way. If the pedestrian walkways and bicycle facilities were safe for local families and baby-boomers, then this topic of urban design would be focused on architecturalstyle, not building height, all by enabling people to have viable transportation options.

Consequently, parking demand would decrease, foot traffic would increase, and local businesses would benefit. Available parking would then be used by tourists and people who live too far away or up in the hills.

Land required to be dedicated to storing cars that people must use for safe travel within a walkable distance could, instead, be used to enhance–not decrease–the commercial value of the property.

But as long as we have on-site parking requirements to enable more people to drive because walking is unsafe, those pedestrian transportation problems will force buildings to be bigger.

Santa Barbara Architect, Henry Lenny, who co-wrote the City’s Spanish Colonial Revival Architectural Design Guidelines and serves as the City’s Consulting Architect, spoke against the 2-story height limitation for architectural reasons. Afterward, I asked him if he thought my analysis was valid.

“You’re exactly right,” Lenny said. “If we can address how people move, then many of these height problems go away.”

So there you have it: size matters. And now we know why.